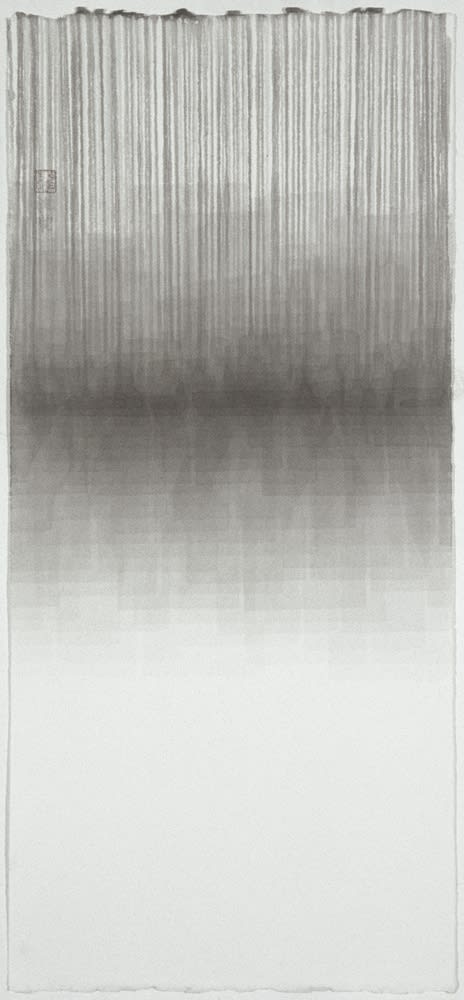

They vary: some have broader bands, brushstrokes, some have narrower; some display a greater range of tonalities from dark to light and some are nearly black or very pale, their composition seemingly allover; some have tinges of color. My first thought was to call these paintings ephemeral. They seemed almost not there, like falls of water or rain or wisps of clouds and other similarly fleeting natural phenomena miraculously hovering just above the canvas. Yet they brimmed with intimations and a slowly emerging radiance, reverberating subtly, so subtly that you might think you imagined the shift in tonality, like the way light can come and go, lightening and darkening imperceptibly, appearing, disappearing. Looking more closely, you see that they are undergirded by a semblance of a grid made by the weave of the brushwork, seesawing between presence and void, or “emptiness and fullness,” as Shen Chen, the artist whose creations these are, likes to put it.

-

Grey Matters

Shen ChenFu Qiumeng Fine Art is pleased to present an exhibition of acrylic paintings and ink work on paper by Shen Chen at the gallery’s 65 East 80th Street Location in New York, marking the artist’s first solo presentation with the gallery. This exhibition will include an unprecedented selection of paintings in the artist’s unique abstract, monochromatic style which is closely linked to the spirituality of Eastern ink.

Shen Chen was one of the leading figures of China’s abstract painting and experimental ink art movement during the 1980s and has devoted his career to exploring the possibilities of ink and the development of abstract art. The Shanghai Experimental Art Movement was an important period before the well-known The 85 New Wave Movement, which documented the Chinese early abstract and experimental art’s transition to the contemporary, a vital turning point in Chinese art history. Shen organized and participated in Wild Rose, the first experimental art exhibition, at the Shanghai Theater Academy (1978), and participated in the landmark 1986 Grand Exhibition – Youth Artists, China National Museum of Art, Beijing. In 1988, he received a scholarship from theSkowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Maine Fellowship Award-Art in Residence and has lived in New York since 1991.

-

-

Untitled No.12303-17,Acrylic on Canvas,40 x 32 inch (101.6 x 81.25 cm)

-

Untitled No.91212-18 Acrylic on Canvas 40X32in. 2018

-

-

Shen Chen’s works have been exhibited at various art museums, including National Art Museum of China, Roma Academy of Fine Arts, Today Art Museum, Queens Museum of Art, Bochum Museum, Shanghai University Museum, Hexiangning Museum of Contemporary Art, Museum of Chinese in America, Epoch Art Museum, Yuan Art Museum,Himalaya Museum of Art, Singer Museum of Art, Kunsthalle Recklinghausen, Museum Hurrle Durbach and ME Collection Berlin. His works are in many public and private collections including ME Collection Berlin (Germany),Aszo Nobel Art Foundation (Netherland), Duke Energy Corporation (USA), Johnson & Johnson Foundation (USA), Today Art Museum (China), Stibbe Collection, (Netherlands), Shanghai University (China), San Shang Museum of Contemporary Art (China), etc.

-

-

Shen Chen, Untitled No.50066-0917, 2017, Acrylic on Canvas, 42 x 48 in (106.7 x 121.9 cm)

Shen Chen, Untitled No.50066-0917, 2017, Acrylic on Canvas, 42 x 48 in (106.7 x 121.9 cm) -

Untitled No.10144-09, Acrylic on Canvas, 48 x 68 inches, 122 x 172.7 cm, 2009

Untitled No.10144-09, Acrylic on Canvas, 48 x 68 inches, 122 x 172.7 cm, 2009The grid, an image/structure closely identified with European and American modernism, signals a sensibility familiar with the art of East and West. That binary that has been operative for centuries, with upswings and downturns, as interaction gives way to disengagement, depending upon a host of geopolitical, economic and social factors. Certainly these days, the encounters between East and West has become far less exotic in our blended era of more or less matter-of-fact globalism, as cultures and countries have become increasingly proximate—in actuality and virtually—thanks to all manner of technological advances. This is true despite the unfortunate world-wide tilt toward less open borders and the concomitant rise in xenophobic policies and nationalist, nativist ideologies that have wakened us from the dream of a golden age of internationalism that seemed imminent only a few years ago.

-

-

Shen in his New York studio

-

Shen in his New York studio -

Not long before that, Shen Chen was given the opportunity to study in the United States and he seized it. He earned an MFA from Boston University in 1990 and attended a number of art schools in New York. He is completely Chinese, he often says when asked whether his work is American or Chinese. But his work is not defined by his origins in any strict or systematic way. Instead, it is derived from a range of works that have been meaningful to him and not by country or culture. It is the offspring, inevitably, of a particular artist’s singular imagination and experience.

One reason that he was so intent on coming to the United States was to see art that he had been introduced to in China but only through inferior reproductions. Arriving in America, he dove headlong, hungrily into museums and galleries, feasting on their collections. He has spoken of his encounters with Mark Tobey and his fine, calligraphic-like markings; Jackson Pollack’s drip paintings and discovering that they were made on canvases laid flat on the floor (which is how Shen Chen works); Franz Kline’s fierce slashes of black, also reminiscent of calligraphy but blown up in scale; Rothko’s enigmatic and very moving color diaphanes; James Lee Byar’s gold-leafed environments and so many others. What was compelling was the kindred spirit he felt in these works that was based not on identity or formalism but on a transcendent spirituality, a kind of existential core that echoed that of Chan Buddhism.

-

His aesthetic lexicon has been gathered from multiple sources, sometimes apparent, sometimes not, a broad net that is one of his works’ great strengths. Perhaps one of the ways Shen Chen manifests his Chineseness is his embrace and acknowledgement of influences, unlike American artists bound to a cultural imperative of originality, afflicted by the “anxiety of influence,” in literary critic Harold Bloom’s memorable phrase. In fact, for Chinese artists such as Shen Chen, in whom cultural memory remains active, ineradicable, the anxiety might be the reverse, that of no influence. In a traditional Chinese or Asian world view, influence was cultivated. And why shouldn’t artists avail themselves of all that captivates their idiosyncratic imagination?—to be then filtered through their own interpretations.

-

-

In addition to materials—exchanging Chinese ink and paper for Western acrylic and canvas—process is the primary content of these works and the direct result of it. He has claimed that he values it more than the finished product. It includes a number of Chinese painting techniques, among them the method of application of brush marks and the selection of strokes, often canonical, as well as the brushes themselves, which are usually Chinese. He paints in layers, intuitively, each painting’s resolution determined by the uniqueness of that painting’s process. Shen Chen also envisions what he wants to paint in advance. It allows him to let the process take over, the qi, the energy, flowing from him to the brush to the support: “Every touch of the canvas becomes a point of inspiration.”

-

Shen Chen, "Untitled No. 81816-11, 2011," Acrylic on Canvas

-

-

Shen Chen has always loved greys, a love instilled while studying and making ink paintings. After he came to America, he temporarily concentrated on color for several years. I have seen splendid instances of these works although their colorfulness might be a point of dispute since they remained limited in range, four colors or so his maximum. They are more expressions of his views on color and lack of color than they are about pursuing the effects of a full palette or about making a colorful painting for its own sake. His paintings are purposefully tonal and he soon returned to shades of grey, with color occasionally added. To him, grey and black are a color and offer infinite gradations of hues. Black also connects him to his beloved ink painting at the same time it forges ahead into personalized terrain and the present.

-

Untitled No.43000-15, Acrylic on Canvas, 48 x 42 inches, 122 x 107 cm, 2015

-

-

Untitled No.91010-18 Acrylic on Canvas 40X32in. 2018

-

-

ABOUT AUTHOR

Lilly Wei, a New York-based independent curator and critic who contributes to many publications in the United States and abroad. She has written regularly for Art in America since 1982 and is a contributing editor at ARTnews and Art Asia Pacific. Wei has also written for Asian Art News, Art Papers, Sculpture Magazine, Tema Celeste, Flash Art, Art Pressand Art and Auction, among others. She also frequently reports on international biennials such as those of Sydney, Cairo, Athens and Reykjavik.

-

Shen Chen